When Europe’s leaders unveiled the Future Combat Air System (FCAS) in 2017, they sold it as the embodiment of strategic autonomy and technological sovereignty; less than a decade later, the flagship programme risks becoming a case study in how not to design a fighter – because no one really decided what war it was meant to fight.

When strategy, doctrine and programmes diverge

Every serious defence effort starts from a brutally simple sequence: define threats, derive foreign policy objectives, set defence and security goals, assign military missions, translate them into operational tasks, match tasks with resources, then – only then – design forces and equipment. In doctrinal terms, equipment planning sits at the bottom of a pyramid of strategic planning; if you start at the bottom, you are no longer doing defence planning but industrial policy in uniform.

The FCAS story in France and Germany inverts that logic. The German 2016 White Paper set out broad ambitions, stressed NATO, EU cooperation and crisis management, but did not identify a clear peer adversary demanding a sixth generation air dominance system; instead, it called for a modern, capable Bundeswehr able to support allies and deter “potential adversaries” in general terms.

In France, by contrast, the 2017–2024 Loi de Programmation Militaire and its successor laws anchored armed forces planning in explicitly national expeditionary ambitions, with RAFALE as the core combat air instrument, and saw FCAS as a future replacement of a tool already central to French external action. The attached doctrine reminds us that any weapons programme should follow from the identification and ranking of concrete threats to sovereignty, vital interests and citizens, then from political decisions on when force might be used, and only afterwards from derived defence objectives and missions. FCAS never passed that test: rather than answering a coherent set of Franco-German strategic questions, it was asked to reconcile two different national pyramids – one NATO centred and hesitant on hard power, one interventionist and autonomy driven – without a shared threat at the top.

An aircraft in search of an enemy

When President Emmanuel Macron and Chancellor Angela Merkel announced FCAS as a Franco German project in 2017, the political narrative emphasised European defence integration after Brexit and the need for a symbolic flagship programme.

In Berlin’s parliamentary debates and strategic documents of the time, however, Germany had no explicitly named state enemy; instead, the language revolved around an abstract spectrum of risks, from terrorism to cyber threats and regional instability, couched within NATO and EU frameworks – despite Russia had already invaded Crimea and intervened in Syria, China’s build up was already in progress, and Trump’s hard lines on Europe were spelled out, already. Yet Germany sought a sophisticated next generation fighter to sustain its aerospace industry and demonstrate European leadership in high end combat air, even as it hesitated to define who the aircraft might ultimately fight.

France entered FCAS from almost the opposite direction: it had a concrete requirement shaped by decades of unilateral or coalition operations from the Sahel to the Levant but wanted to share the very high costs of a successor to RAFALE, whose export success nonetheless underwrote its own strategic freedom. This raises the central question: what enemies do France and Germany truly intend to fight together with FCAS? Berlin has anchored its defence in NATO collective defence and EU crisis management, often constrained by parliamentary scepticism toward high end combat operations, while Paris has championed strategic autonomy and, famously, Macron’s “brain dead” criticism of NATO’s political cohesion in 2019. Without alignment on the nature, geography and political conditions of future combat, FCAS became less the answer to a shared operational problem and more a canvas on which each capital projected its own, often divergent, strategic anxieties.

A fight between partners, not peers

The industrial politics have been as unforgiving as any dogfight. Germany, after decades of under investment in defence and erosion of high end design skills, saw FCAS as a vehicle to restore know how, secure workshare for Airbus Defence and Space, and escape dependence on foreign designs. France, whose industry – and especially Dassault – had actually delivered and exported a modern fighter on time and on budget, feared a repeat of earlier Franco German programmes in which divergent requirements and export control regimes hamstrung operational utility.

This asymmetry bred mutual suspicion. Disputes over intellectual property ownership, especially in flight control systems and systems integration, delayed the Phase 1B demonstrator contract, and French actors repeatedly accused their German counterparts of seeking to extract Dassault’s hard won expertise under the cover of “balanced” workshare. In parallel, German political constraints on arms exports - from Saudi Arabia to other sensitive markets - fuelled French concern that any jointly developed fighter would be commercially crippled by Berlin’s veto power, precisely at a time when RAFALE exports were becoming the backbone of France’s defence industrial base.

Recent years have only strengthened Paris’s hand. RAFALE orders from the United Arab Emirates, Greece, Croatia and additional Indian and Egyptian deals have extended production well into the 2030s and likely the 2040s, generating a steady revenue stream and sustaining critical design and manufacturing skills. Empowered by this export success and by a national military planning law that assures domestic demand, French industry has adopted a more assertive posture inside FCAS negotiations, less willing to concede core design authority in exchange for German funding that no longer appears existential.

The pillar that may fall

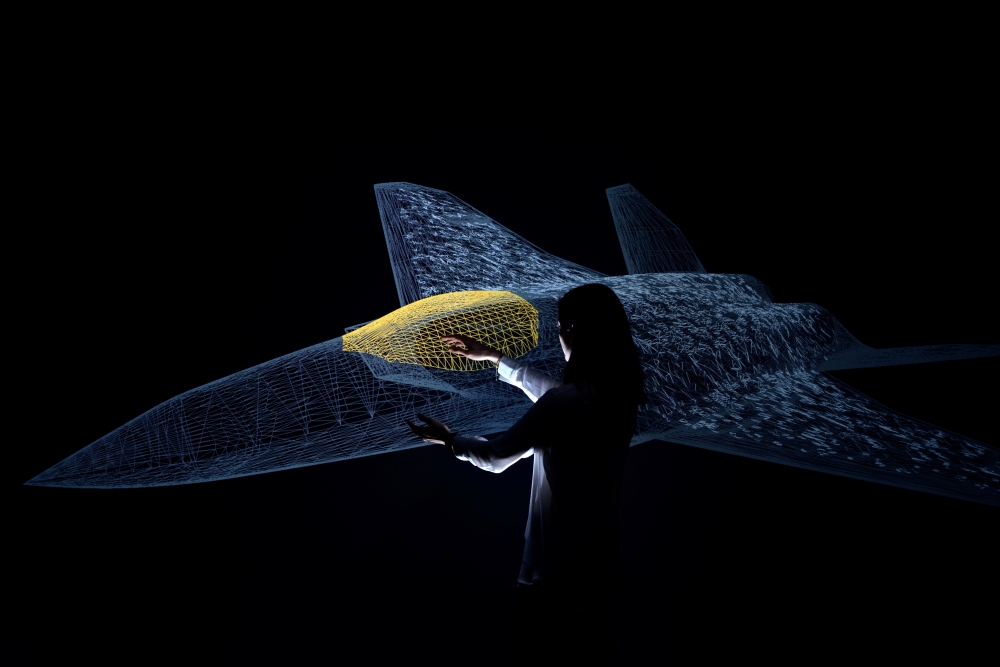

FCAS has always been conceived as a “system of systems”, combining a manned Next Generation Fighter (NGF), remote carrier drones and a combat cloud. As the programme falters, a scenario increasingly discussed in European circles is the cancellation – or radical reshaping – of the first pillar, the manned fighter, while preserving work on the enabling pillars such as sensors, networks, effectors and collaborative combat architectures.

From an industrial standpoint, such a partial continuation would have logic. It would allow European firms to advance in command and control, data fusion, electronic warfare and unmanned teaming – areas where future value and export potential are high – without forcing immediate resolution of the politically toxic questions of cockpit configuration, national champions and ultimate operational control.

But doctrinally, it would perpetuate the same fundamental flaw: investing in exquisite capabilities without a shared, legally grounded understanding of who the enemy is, what missions the combined forces must perform, and under which political authorities and alliances they will fight.

In practice, France might increasingly shape NGF to its own expeditionary template (including the need to ensure the airborne component of its nuclear deterrent and a carrier launched version), while Germany treats the non kinetic and networking components as generic contributions to NATO and EU frameworks; Spain, meanwhile, is left balancing between them, with limited influence over foundational assumptions.

The risk is a “zombie” programme – neither fully alive nor dead – that consumes budgets under the banner of European cooperation while delivering sub optimal tools to aircrews who will have to survive in the most lethal air environment since 1945.

Back to base principles

The doctrine in our opening paragraph offers a clear yardstick for any future decision on FCAS: start with threats, then foreign policy objectives, defence goals, missions, operational tasks, resources, and only then equipment. If Berlin and Paris want a common fighter – or even a common combat air ecosystem and separate fighters – they must first reconcile their threat assessments, from Russia and its long term trajectory to Indo-Pacific dynamics, to terrorism and grey zone coercion, and decide where and when they are genuinely prepared to fight together.

For the French: yes, together, not necessarily under the French command at all times. You will be surprised that plenty of other countries can do it properly, it is not a French prerogative only (non, vous n'êtes pas toujours uniques et spéciaux).

For the Germans: yes, war, that phenomenon in which you shoot down enemy fighter jets, kill other men, bomb enemy targets, suffer losses, W-A-R (Krieg, alles klar!?). The defence industry serves the Armed Forces and enables them to fight – and possibly win - it is not just a highly profitable trade opportunity.

Only once those questions are answered through transparent strategic planning and parliamentary mandates can a next generation fighter be honestly specified as a military solution rather than as an industrial compromise. Otherwise FCAS – whether in its full form or as a torso of surviving pillars – will remain a costly misallocation of taxpayers’ money, driven by prestige, workshare and symbolism more than by the imperative to give pilots and ground crews the best possible chance of surviving the wars of the 2040s and beyond. In that case, we would not lament the death of a programme, but the failure of Europe’s leaders to remember that in defence, planning and strategy must always precede metal and silicon.